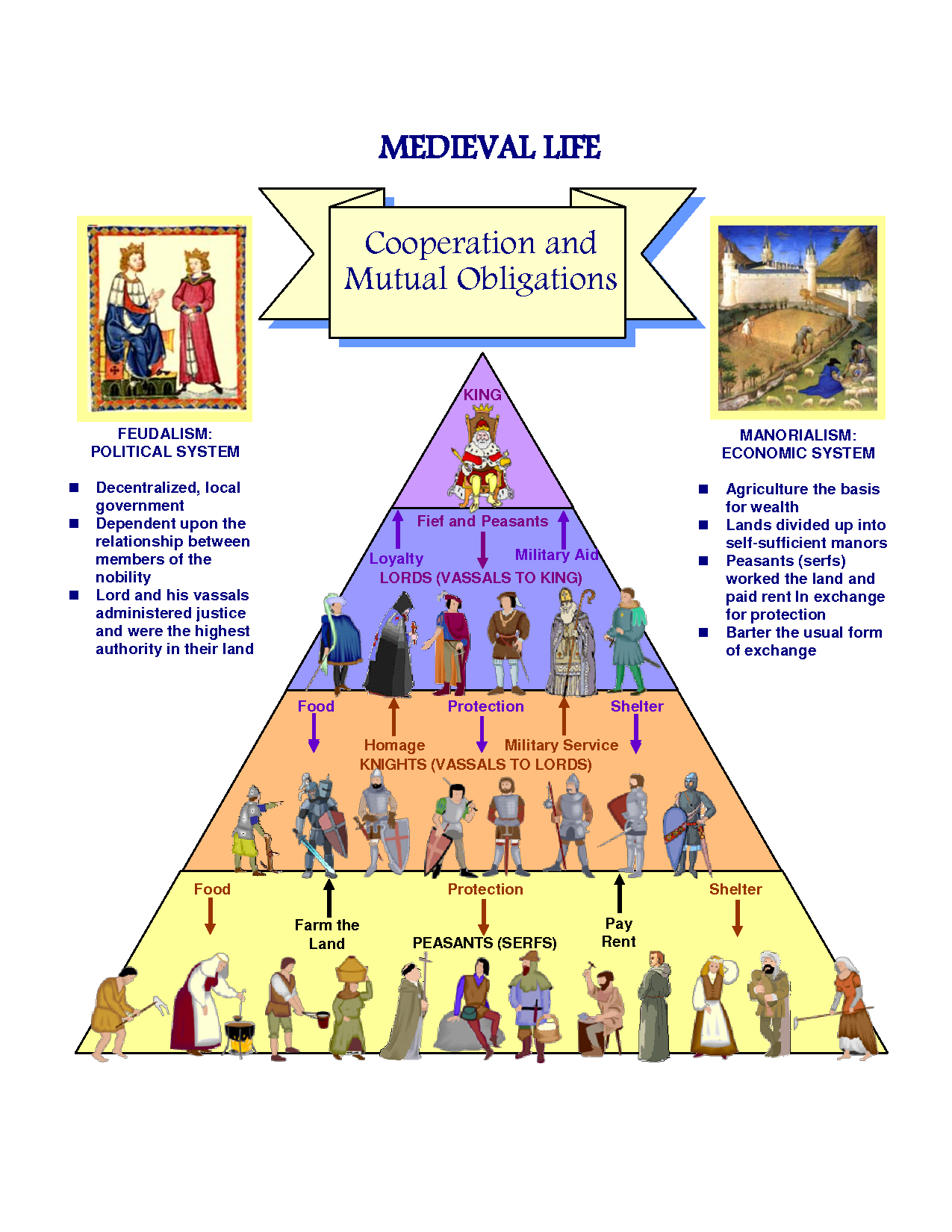

These obligations included military service, hospitality, castle defense, and payments to the lord during times of festivities. Vassals were bound by the contractual obligations that established feudal relationships. An early 12th Century account of the “murder of a feudal lord” includes the terrified statement of a young knight: “Heaven forbid that we should betray our lord and the count of our land…” In Dante’s Inferno, for example, the lowest level of hell is occupied by Judas who betrayed Christ and Brutus who betrayed Julius Caesar. Dante Alighieri, the great poet of the Middle Ages, reminds readers that the greatest sin was the act of treachery, the betrayal of one’s lord. The obligations of a vassal to his lord involved fidelity and homage. This relationship was both complex and pliable, changing through the centuries and adapting to new constrictions such as a hereditary fief.

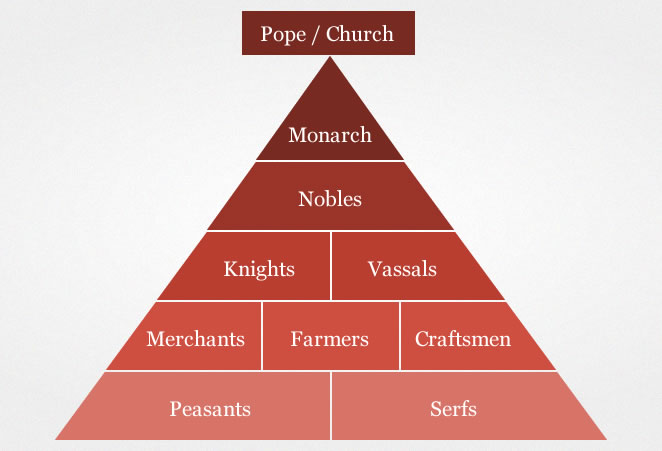

But this is only one piece of the puzzle that made up the greater fabric of feudal obligations as they related to military and social considerations. Hence, early medieval communities relied on localized forces to combat the Vikings when they struck. Large armies that took time to organize were ineffectual against the swift raids of Vikings. Tierney and Painter note that increased Viking raids following the death of Charlemagne in CE 814 may have contributed to the military aspects of the system in order to emphasize “locally improvised protection.” The granting of land (a fief or benefice) entailed service to the lord. At the top was the king while the knight or chevalier was found at the bottom. Some historians note that the feudal system was like a pyramid. By the 9th and into the 10th Century, those relationships governed detailed obligations, often over-lapping between various lords, and defined by property, law, and inheritance. Historian Steven Ozment states that, “As large numbers populated the countryside, there evolved that peculiar fusion of Germanic, Roman, and Christian practices that we speak of today as “feudal society.’” Feudalism represented the relationship between lord and vassal. But historical research demonstrated that the presuppositions governing the use of the term dark ages were false: Western Europe in the Early Middle Ages did experience a degree of learning trade had not ceased and law prevailed – albeit a legal system influenced by the Church, the barbarians, and scraps of Roman law. In rudimentary form, feudalism was a part of those dark ages. Hence, feudalism cannot be properly understood simply as a generalization or through the prism of independent historiography focusing solely on one aspect of the system.Ī partially relevant example might be the discarded use of the term “Dark Ages” to label the period of the Early Middle Ages. Attempting to Define the Feudal “System”įeudalism in France was different from feudalism in England, and this, according to medieval historians, may account for the eventual emergence of societies tied to different concepts of law, social relationships, and royal power.

The notion of a feudal lord and his vassals, for example, is part of that overall system, although the specifics beyond generalizing must account for geographic differences as well as other factors. The so-called “feudal society,” however, can refer to various elements of that transformation period, including social relationships, the economic and legal systems, and the impact of Christian influences. Feudalism, as a generalization, describes those forces in Western Europe during a period of transformation following the dissolution of the Roman Empire.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)